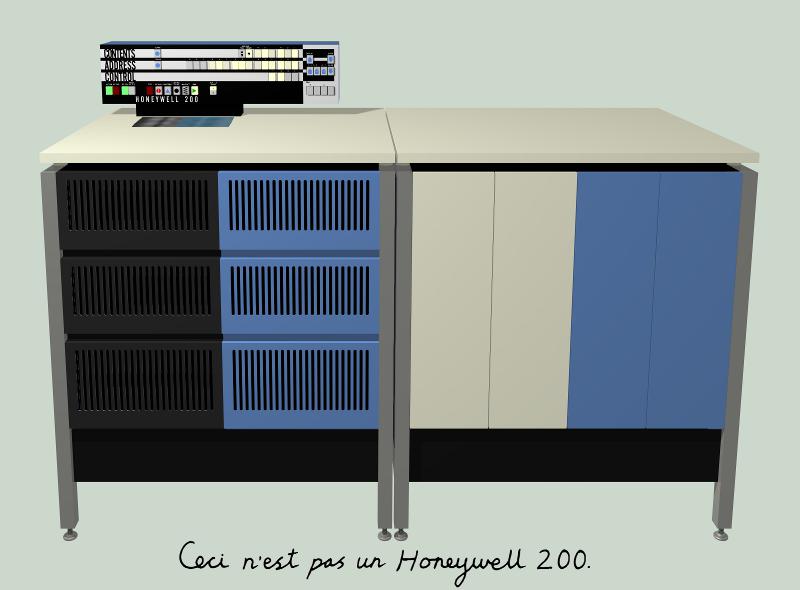

Here

is a picture of a small Honeywell 200 installation using just punched

cards. Building all this would be a challenge, so which part should

be regarded as the actual computer?

Here

is a picture of a small Honeywell 200 installation using just punched

cards. Building all this would be a challenge, so which part should

be regarded as the actual computer?

On the near right of the picture the two boxes one on top of the other are a model 224 card reader/punch, but the mechanism for this was allegedly actually made by IBM so it could hardly be regarded as a key component of the Honeywell 200 proper.

On the near left is a model 222 line printer, a beast capable of eating boxes of stationery at a fearsome pace. In the instructions for this device the operator was advised that in the case of a paper runaway the printer could be stopped by diving down and tearing the paper apart where it entered the machine. Printing involved 132 hammers banging the paper against a long spinning drum embossed with the typeface and the energy needed to do this was contained in a bank of capacitors, which was treated with great respect by the engineers for fear of having a misplaced screwdriver melted. Another potential fate was to be dragged into the machine by one's tie while leaning over the mechanism. The replica computer probably doesn't need one of these.

Further along on the left is a model 223 card reader, a distinctive design with a triangular cabinet and an unusually angled card hopper which was very practical in use. If any peripheral device reflected the style of the Honeywell 200 itself it was probably this one. The design was simple and effective and if punched cards were to be considered as a medium for the replica then it probably wouldn't be beyond the ability of someone with engineering skills and resources to build one, but it must unfortunately be considered outside the scope of the current project, especially since punched cards themselves no longer appear to be available.

Over to the far right the computer's control panel can be seen perched above the worktop, so the computer itself must be there somewhere, but first look at the room as a whole to understand the nature of the machine. The equipment cabinets were low, providing useful work surfaces for the people, who in turn weren't dominated by equipment towering over them. They could almost be using kitchen appliances rather than a mainframe computer. To the left can be seen long picture windows where passers by could watch the machine in operation. Indeed, as the floor was raised to conceal all the underlying cables connecting the devices it appeared to onlookers as though the whole room was a set on a stage, which together with the apparently meaningless flashing lights on the clearly visible control panel gave the illusion of a performance, adding an air of mystery. In the 1960s companies spent serious amounts of money on mainframe computers and consequently even small machines like this one had a special status.

There was also another aspect to the room which can't be seen in the picture; it was an American room in a British building. Beyond those windows there was a traditional British office set in the middle of Tunbridge Wells, a place where the staff were still called by their surnames, the electrical supply was 240 volts at 50 Hertz, there was no air conditioning and the money was pounds, shillings and pence. Inside this room had full air conditioning; the temperature had to be closely controlled as the central processor was sensitive to variations and the humidity also needed to be kept in check or else the 223 high speed reader might choke on cards affected by the damp British climate. The electrical supply was American standard 120 volts at 60 Hertz supplied by a rotary converter located directly above the room and – well where money was concerned even an American computer had to make concessions, but it needed help from us programmers who fed it with programs, not programmes, and called people by their first names, a practice which quickly spread around the rest of the office. Was this what I remember about the machine, not its own style but the influence that the Honeywell company had on us overall? No, there's more to it than that.

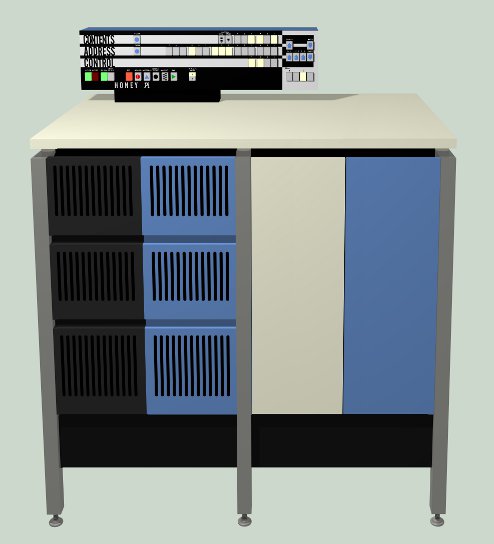

This

is a picture of the computer itself, not a photograph but a computer

generated image as there aren't any clear colour pictures of it that

I've found so far and anyway this website is about a replica, so my

impression of what a replica would look like is the important thing.

One would guess that the central processor was in the cabinet under

that distinctive control panel, but that only contained the

electronics for the panel itself, switchgear and power supply units,

hence the ventilation. The central processor and memory were actually

in the more mundane cabinet on the right. That cabinet had four logic

drawers, two containing the central processor and two the memory, up

to 32k bytes in total. The colours of the drawers signified their

different contents but I'm not sure what the colours actually were.

This

is a picture of the computer itself, not a photograph but a computer

generated image as there aren't any clear colour pictures of it that

I've found so far and anyway this website is about a replica, so my

impression of what a replica would look like is the important thing.

One would guess that the central processor was in the cabinet under

that distinctive control panel, but that only contained the

electronics for the panel itself, switchgear and power supply units,

hence the ventilation. The central processor and memory were actually

in the more mundane cabinet on the right. That cabinet had four logic

drawers, two containing the central processor and two the memory, up

to 32k bytes in total. The colours of the drawers signified their

different contents but I'm not sure what the colours actually were.

Disregarding functionality the simple style of the design is immediately apparent. The strong use of colour and combinations of horizontal and vertical geometry in the cabinets was topped off in a similar way by the control panel. Functionally the main buttons on the panel had prominent symbols on them to signal clearly the status of the machine across a room while the textual descriptions were relegated to the margins. Also note how the normal control buttons were contained within the main body of the panel while the controls for modifying the behaviour of the machine were placed jauntily off to one side, as though implying that any interference by the operator would mar the perfectly balanced performance of the machine. This is just artistic interpretation of the design though as the truth may simply be that the supporting column couldn't extend beyond the centre line of the cabinet because there was something in the right hand compartment below which got in the way. Nevertheless visually the design was right at home in Britain in the 60s and one feels that there should be a girl in a Mary Quant outfit in the picture. I'll keep my camera handy in case someone volunteers but it isn't essential to the project. Certainly the overall appearance of the machine promised that attention had been paid to detail in every aspect of its design though.

The

replica computer could be housed in cabinets similar to the

originals, but the limited supply of components available and their

different technology means that they will take up less space, so a

smaller cabinet something like that shown here would be more

practical without losing the character of the original machine. The

objective is that the replica will meet at least the minimum

specification of a type 201 processor and include as many of the

optional features as is practicable. In contrast the original

cabinets provided space for all the modular features offered by the

type 201, 201-1 and 201-2 processors.

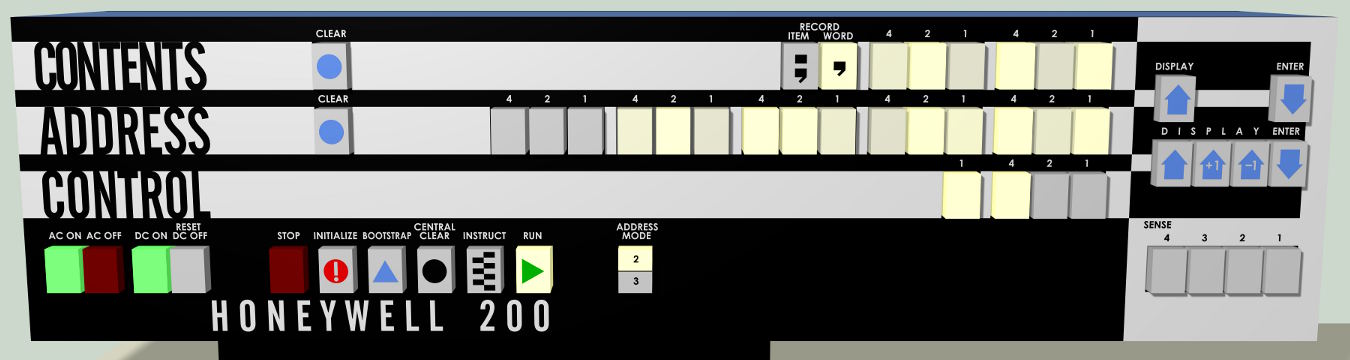

Now a closer look at the control panel. Once again this is not

a photograph of the real thing.

The layout of the panel was virtually self-explanatory to anyone who knew the internal architecture of the machine. Apart from the protruding buttons it was flat with no unnecessary features to disrupt the printed artwork. In the data display portion the finger-width buttons arranged in threes could easily be used by the operator to enter octal values like a pianist playing chords. Translations of the octal codes were provided on a printed chart attached to the worktop directly in front of the panel so that it was unnecessary to consult a manual for a forgotten code. This was a relatively low cost machine economically built but that didn't mean that it was difficult to use. Note that there were no visible error indicators on the uncluttered panel. The machine didn't normally admit to the possibility of a malfunction but in the event of one being detected a message would light up in the apparently opaque black lower section like a rash on a person's skin. In addition a normally white button might blush red, awaiting diagnosis. Other machines in the extended 200 series used a console typewriter in place of the basic control panel and although that was a more versatile interface it didn't project the same sense of style that this panel had, so the replica will definitely have as accurate a reproduction of the panel as is possible.

The Honeywell 200 wasn't intended to be "big iron", a large number crunching superfast mainframe, an express train of the computing world; instead it was designed primarily as a shunting engine, capable of moving packets of data from place to place, whether as the front end device for a larger number cruncher or in its own right as a modest commercial computer passing data from storage media to everyday printed documents. As a result its strength was in the modularity of its design and its ability to handle peripheral devices and their data. For that reason we must return to the question of what the computer actually was and whether the replica will reproduce that. To demonstrate that it does it will need peripheral devices that are practical and yet of an earlier age, so candidates being considered are magnetic card reader/writers in place of punched card devices and serial printers in place of a line printer. Also, to give a taste of an even earlier age paper tape readers and punches from the first generation era of relay-operated devices may be included eventually. However, regardless of the applications that the original designers anticipated for it, this machine was versatile enough to do much more and this project will set out to prove that.

Finally, while referring to the original designers I must mention the late Dr. William L. Gordon who headed up the original design team at Honeywell. His daughter told me that he often used the word "elegant" and that she wanted to know how it applied to this computer. That was it, the word that summed up what I felt about the machine myself. All I have to do is prove that the feeling was justified and that he was right.